Could the moon’s phases help us connect better with ourselves?

It’s already light at 6.30am on a crisp, clear summer morning as Dr Hinemoa Elder (Ngāti Kuri, Te Rārawa, Te Aupōuri, Ngāpuhi) drives to the ferry from her home on Waiheke Island, headed to Starship Children’s Hospital where she works as a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Hina (the Māori moon goddess) is directly in front of her, lighting her path. Hinemoa searches her knowledge of the maramataka – the Māori lunar calendar – to recall which of Hina’s 30 different faces she sees.

“It’s the first clear morning for quite a while. You can see Hina’s changing shape. She’s been in her full beam state – Rākaunui and Rākaumatohi – she’s been gradually going to the Korekores. That brings up lots of issues around my own health and wellbeing and female health. Today’s about Hinenuitepō and the pelvic floor – that makes me giggle a little bit as I’m driving along in the car thinking about pelvic floor muscles.”

Hinemoa hasn’t always been so connected to Hina. Growing up, her mother told her not to do things ‘the Māori way’ – typical advice from a Māori parent in the era when te reo Māori was under threat and Aotearoa’s revitalisation of mātauranga Māori was still decades away.

‘They were her words, but her emotions were saying the complete opposite, and we could feel that from her very powerfully. There was a sense of suffering that, in a way, has stayed with me and has given me pause to reflect in different ways over my life since then.’

Over the past few decades, Hinemoa has been on a journey to learn more about her Māori identity. One way of doing that was to connect with the maramataka (Māori lunar calendar) or okoro, as her Far North iwi Te Aupōuri calls it. She’s bringing this ancient wisdom into personal and professional daily life and using it to consider the world around her and her wellbeing.

In late 2022, she published Wawata Moon Dreaming, a guide for people to connect to the maramataka. In it, she wrote, “This is the book I wish I had read when I was young.” She hopes the next generation will feel more connected to their ancestors’ wisdom and the earth, sea and sky.

Ancient wisdom

Before colonisation, Māori lived by the moon. Each iwi followed its version of the maramataka, with 12 or 13 lunar cycles a year, culminating in Matariki, the Māori new year. In different ways iwi have continued these practices.

Traditionally, gardening and fishing practices were dictated by Hina, who advised when it was the best time to plant new crops and harvest kaimoana, and when to let taiao rest. The maramataka also guided Māori in their personal and collective hauora, telling them when to celebrate, work hard and rest.

But this knowledge was lost to many until Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori Māori Language Commission began its mainstream revival in 1990. The transliterations of English names, such as Hanuere for January, were dropped and replaced with traditional names provided by Tūtakangahau of Maungapōhatu (Ngāi Tūhoe) and a maramataka expert.

Hinemoa has been collecting knowledge of the maramataka since the early 2000s, and for many years she kept a personal maramataka diary. In this diary, she recorded how she felt mentally, emotionally and physically as Hina cycled through her 30 faces. In the mid 2000s, one of the first guides to the maramataka was commercially published.

“I remember buying copies of that for my team with the idea that these were resources that would encourage us to think about time through a Māori lens. It’s been extraordinary to see how the resources around that have grown immensely since then.”

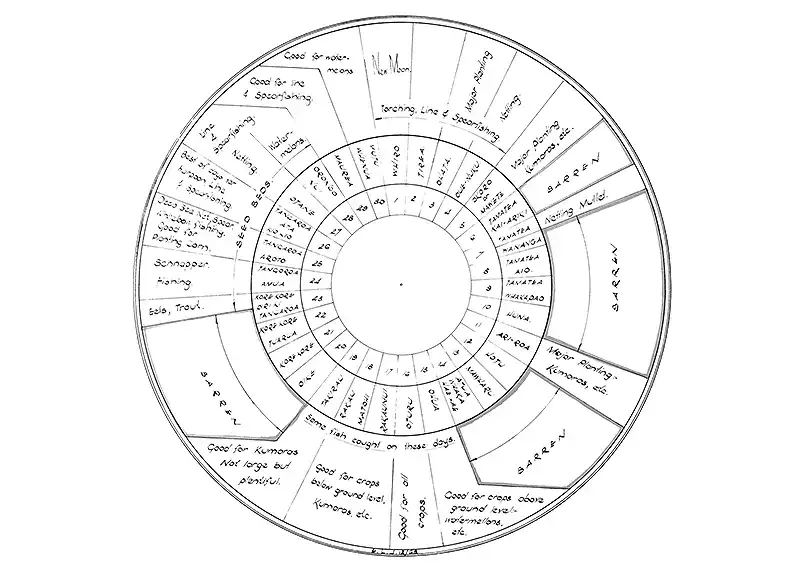

In 2020, she made a remarkable discovery at her cousin’s house that gave her maramataka journey a sense of personal destiny. There on the wall was a 50-year-old maramataka, hand drawn in 1969 by her whanaunga Ted Jones. Ted had created the chart on the instruction of his grandmother Raiha Moeroa Jones and the esteemed Māori navigator Tā Hekenukumai Busby. The circular calendar dictated the 30 names of Hina throughout the month, as well as instructions for catching kaimoana and planting and harvesting crops.

Seeing this gave her inspiration for her book, Wawata – Moon Dreaming. She wants us to see maramataka as more than a lunar calendar of good and bad days for fishing, planting and harvesting. For Hinemoa, maramataka is a starting point for a deeper understanding of our own personal wellbeing.

A hand-drawn 50-year-old maramataka set Dr Hinemoa Elder on a journey of discovery.

The maramataka guided Māori on the best times to plant crops.

Writing Wawata

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, Hinemoa set to work writing Wawata, a book that combines the ancient mātauranga and storytelling she has collected with her personal experiences. It explores each day of the moon’s cycle, illustrating how to connect with ourselves and others.

She used her whanaunga’s maramataka as the basis and wrote the section on each of Hina’s faces only on the day it was present in the sky, allowing Hinemoa to harness the energy and feeling of that moon phase.

“I’ve illustrated my personal experiences that have come together through reflecting on each different day over many years. But I didn’t want to be too prescriptive to the reader, to use that as a springboard and offer an opportunity to reflect on what they find useful.”

Hinemoa hopes the book will inspire a connection with te taiao and introspection and reflection in readers. She says it’s a book designed to be referred back to, with space in the margins for notes, pages dog-eared and passages that resonate underlined.

Discovering connection

In her work as a psychiatrist, Hinemoa says she has seen the ongoing impacts the pandemic has had on healthcare professionals who are tired and burned out.

“For me as a psychiatrist, I’ve needed to draw on cultural resources for my mental wellbeing and to help us navigate the immense complexities that we’re faced with.”

She says healthcare professionals are responsible for looking after themselves first and foremost.

“One good thing that can come out of this multifaceted COVID experience is the clear imperative for a much better, more robust system of care for healthcare professionals than we had before.”

Hinemoa says a simple way to reconnect with your hauora and take a moment for yourself could be to think about Hina – where she is in her journey and how she impacts our wellbeing on that day.

Gaining perspective

Society has much to gain from te ao Māori knowledge and perspectives, Hinemoa says. “In colonisation, there is a tendency to dismiss other forms of knowledge that are not determined by a particular research design methodology and hierarchy.”

Adding Matariki as a public holiday – one of the only indigenous national holidays in the world – gives mātauranga Māori a bigger platform, and encourages more understanding of the Māori worldview, she says. "Thinking about our navigational practices, for example. We didn’t come here by mistake or by accident. We planned to come here. We had the technology, we had the science, our own mātauranga that has helped people travel back and forth across Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean) over thousands of years.”

Another example of this is Sir Mason Durie’s concept of Te Whare Tapa Whā, a way of considering health holistically by thinking about physical, mental, spiritual and whānau working together. She says that the maramataka can complement and build on the idea of Te Whare Tapa Whā in considering how we perceive time.

“From a Māori perspective – and I’ve talked about this quite a bit in the book – we can experience the past, present and future all at the same time. We have a very different relationship with time in te ao Māori where we’re not able to control time, so we don’t think about fighting with time or racing against time or having this adversarial relationship with time.”

By becoming aware of the maramataka, we can consider time differently – knowing each of Hina’s faces follow in the same order every month, and challenging days will be followed by days of rest and peace, she says.

But this can be at odds with the Western education and work systems, so more cultural competency is needed.

“For those of us who are practising medicine here in Aotearoa, we do need to be culturally competent. We need to know how to work with our Māori whānau and patients, and I know that’s often pretty challenging. It’s challenging for me sometimes as a Māori psychiatrist, and I know it’s challenging for many of my non-Māori colleagues.”

She hopes Wawata, along with other resources provide safe spaces for healthcare professionals to reflect on how they can “bring greater awareness, build rapport with Māori patients and whānau, and demonstrate to them that they are carefully and respectfully attempting to be good te Tiriti practitioners of care in this country”.

Know someone who might enjoy this?

Read this next

-

March 2021

Manaakitanga – more than just hospitality

-

July 2022

Climate change through a Māori lens

Greater good

See all-

March 2021

Candles for a cause

-

March 2021

Helping Kiwi babies thrive

-

March 2021

Creating a Deaf-inclusive Aotearoa