The first few months of a baby’s life is hard work for parents at the best of times, and it can be even harder if breastfeeding is a challenge. With support from the MAS Foundation, two University of Auckland medical students have been shining a light on the provision of breastfeeding support and education across New Zealand.

For years, mothers have been told that “breast is best” when it comes to feeding their newborns.

UNICEF recommends breastfeeding babies exclusively – without other foods or liquids – for the first six months and that mothers continue to supplement a child’s diet with breastfeeding until two years of age. On top of this official advice, media portrayals of mothers and their babies also frequently fixate on breastfeeding as a blissful bonding experience between mother and child.

The reality can be very different for many mothers. While about 80% of Kiwi babies are fed exclusively on breastmilk in the first days of life, this drops to 49% six weeks after birth and to 17% at six months. For some mothers, breastfeeding never becomes established for all sorts of reasons, including difficulties with latching, painful feeding, nipple damage and insufficient milk supply.

Given the emphasis on the health and bonding benefits, difficulties establishing breastfeeding can be very distressing for mothers.

To make things more complicated, breastfeeding support services vary across the country. Public funding for lactation support is available for six to nine months in some regions but ends after six weeks in other areas – just when issues such as insufficient baby weight-gain begin to emerge.

Supporting mums and babies

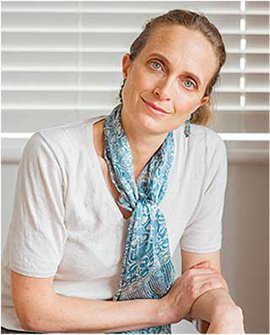

Breastfeeding specialist and lactation consultant Dr Abby Baskett is committed to helping mothers and babies get off to a good start with breastfeeding.

The Paediatric Emergency Specialist at Starship Children’s Hospital holds weekly private breastfeeding clinics, which were born out of a lack of options for women needing next-level support for difficult breastfeeding problems.

“The clinics are always full, and women regularly arrive desperate, recounting similar stories about struggling to find support."

Dr Abby Baskett

Abby says she’s acutely aware that, for every woman she helps, many more are unable to pay for the support they need and can face waiting lists for publicly funded services, assuming they exist in their area at all.

These inequities motivated her to pursue a research grant from the MAS Foundation.

“I want all mothers to receive the same level of care, particularly those from lower-income families who stand to gain the biggest benefits from breastfeeding,” she says.

Boosting breastfeeding education

Part of Abby’s research focuses on breastfeeding education in relevant health science degrees an area where she is pressing for change.

“GPs are often the first port of call for mothers with breastfeeding issues, but unless they have a special interest, their training in this area is minimal. Most midwives can deal with basic breastfeeding issues, but not all of them are qualified lactation consultants.

Problems arise when next-level support is needed for more complicated issues,” she says.

“What’s needed is a publicly funded specialist breastfeeding service that GPs and midwives can refer mothers to, which provides regular clinics for mothers and babies regardless of their postcode. This would also create an opportunity to centralise breastfeeding knowledge and deliver a consistent standard of education.”

Research underway

But first a review of what’s currently available is needed. Third-year University of Auckland medical students Rachel Baker and Carolyn Matthew are working with Abby to establish the current state of lactation support training and services in New Zealand.

As part of the university’s Summer Internship Research Programme, which gives students the chance to spend 10 weeks working on a research project aligned to their studies, Rachel and Carolyn have been helping Abby with two main research questions.

One question focused on what sort of breastfeeding training was provided as part of broader medical, nursing and midwifery courses at institutions around the country.

The other part of the research looked at the nature of publicly funded breastfeeding support services available to women via district health boards around New Zealand as well as exploring the services available for babies with tongue tie.

One Mother’s Story

A mother shares her experience in trying to breastfeed a child and the challenges in finding help when it didn’t come easily.

I’m someone who copes pretty well with what life throws at me, but the weeks following the birth of my second child are firmly etched on my mind and feel devastating to this day.

With my firstborn, I had mastitis. The pain was excruciating. I got through it, but the horror never left me. The women in my coffee group all had issues. We used to joke that there must be a secret society responsible for a major cover-up about how hard breastfeeding is.

Six weeks after my second child was born, some familiar symptoms kicked in. Things quickly went from bad to worse, and I felt like I’d been hit by a freight train. My midwife care had ended, but I phoned her anyway. She assured me that Birthcare would be able to help. I rang Birthcare and got a receptionist. It was a Friday, and they had no appointments until the following Monday. I was so choked up I couldn’t get any words out. After a long pause, I think I must have just hung up.

I tried my GP surgery but couldn’t get a same day appointment. I considered going to the emergency department at my closest hospital, but sitting around for hours in terrible pain with a newborn while still recovering from a caesarean just wasn’t an option. I felt like every door was shut.

In desperation, I phoned my sister, who works at a women’s healthcare centre. She managed to get me in to see a breast physician. I have this vivid memory of sitting there, holding my baby and sobbing uncontrollably. I’ve never felt so broken. Luckily, I had insurance to cover the treatment I needed, but I should never have ended up there.

Pregnant with my third child, I was determined that this wouldn’t happen to me again. I went to see a lactation consultant soon after my son was born. It was a revelation. The techniques she showed me made feeding so much easier. I felt saddened at what I’d suffered in the past. Things would have been so different if I’d had the help I needed from the start. You’d think there would be much better support available for something as important as feeding your baby.

Know someone who might enjoy this?

Read this next

-

March 2021

The great brain gain

-

March 2021

Creating a Deaf-inclusive Aotearoa

-

March 2021

Manaakitanga – more than just hospitality

Greater good

See all-

March 2021

Candles for a cause

-

March 2021

Creating a Deaf-inclusive Aotearoa

-

July 2021

Rebuilding after the Lake Ōhau fire