Our oceans are being depleted of fish at an alarming rate. Here’s how you can make a difference.

By Sharon Stephenson

There’s plenty more fish in the sea, goes the saying.

But according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization 70% of the world’s fish population is either fished at its limit, overfished or in crisis.

Blame it on global seafood consumption, which is estimated to have more than doubled in the past 50 years.

Unsurprisingly, scientists predict that, if we continue to fish at this rate, the world’s fisheries are at risk of collapse, which could threaten not just livelihoods but also the health of the 3 billion people who rely on fish as a significant part of their diet. With the world’s population projected to grow by 33% by 2050, requiring production of 70% more food to meet demand, a threat to fish stocks is a threat to global food security.

Enter sustainable fishing practices, which economists and conservationists say we’ll need to employ if we want to continue to rely on the ocean as an important food source.

Increasing awareness

Martin Bosley (pictured) knows better than most the impact of declining fish stocks. The chef and former owner of his eponymous Wellington seafood restaurant is now National Sales Manager for seafood company Yellow Brick Road. He believes we’re fortunate in Aotearoa that our fishing stocks are managed by MPI’s Quota Management System.

Martin Bosley (pictured) knows better than most the impact of declining fish stocks. The chef and former owner of his eponymous Wellington seafood restaurant is now National Sales Manager for seafood company Yellow Brick Road. He believes we’re fortunate in Aotearoa that our fishing stocks are managed by MPI’s Quota Management System.

“Love it or hate it, that system means all our fish in New Zealand is sustainable and not overfished,” says Martin, “and we are one of the few countries in the world to still have wild fishing, rather than completely farmed fish, so we’re in a better place than many countries.”

But he says consumers still need to be aware of how their fish is caught. “We should be asking at the fish counter if the fish was line caught or by trawling because trawling is inherently bad. With line fishing, it’s one hook, one fish and less by-catch so it’s far more sustainable.”

Yellow Brick Road, which supplies seafood directly to more than 180 restaurants, won’t touch any fish if “we don’t know who caught it, where it was caught and how it was caught”.

“That provenance is important to us and it should be to consumers too.”

Choose differently

Martin suggests widening our palate by trying some of the less popular fish. “We have more than 600 species of fish in New Zealand, not just snapper, tarakihi and hāpuka. But people get to the fish counter and freak out if there’s fish they don’t know.”

MARTIN BOSLEY’S ALTERNATIVE FISH SUGGESTIONS

Alfosino: This white fish with a firm texture is a great replacement for snapper and goes well in sashimi or the Pacific dish of ika mata marinated with coconut cream and lime juice.

Alfosino: This white fish with a firm texture is a great replacement for snapper and goes well in sashimi or the Pacific dish of ika mata marinated with coconut cream and lime juice.

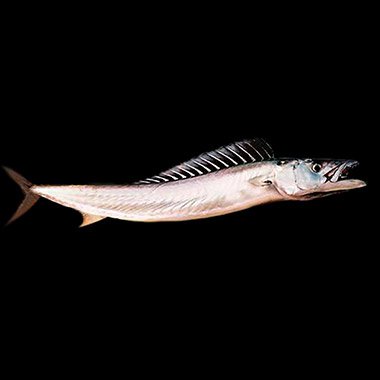

Gemfish: This fish has delicate flesh that flakes easily. It suits Mediterranean ingredients and is great pan fried or in a kedgeree.

Gemfish: This fish has delicate flesh that flakes easily. It suits Mediterranean ingredients and is great pan fried or in a kedgeree.

Ling: This is a great substitute for hake or hoki and has very firm white flesh that holds its shape well. It’s highly versatile, and if you’re hankering for a fish stew, this is your fish.

Ling: This is a great substitute for hake or hoki and has very firm white flesh that holds its shape well. It’s highly versatile, and if you’re hankering for a fish stew, this is your fish.

“My advice would be to educate yourself. Up until recently, we looked down on trevally, but it’s one of the most popular fish we export to Japan so it’s time we started to see it in a different light.”

Geoff Keey (pictured), Strategic Advisor at Forest & Bird, agrees that if we are to work towards a more sustainable future, there needs to be a major change to the way fish ends up on our plates.

Geoff Keey (pictured), Strategic Advisor at Forest & Bird, agrees that if we are to work towards a more sustainable future, there needs to be a major change to the way fish ends up on our plates.

“First, we need to have more marine protected areas around New Zealand where fishing can’t take place, which will ensure healthy ecosystems,” says Geoff. “Places like the Hauraki Gulf and the ocean around Rangitāhua/Kermadec Islands, which are currently being considered for protection from fishing.”

He advocates the end of bottom trawling which “smashes up everything in the nets’ path”, and a shift to ecosystem-based fisheries management so all species are considered when looking at what the ecosystem needs.

“At the moment, each species is individually assessed, but Forest & Bird is asking that we turn the current system on its head and look at the whole ecosystem and what every species that lives there needs before we can assess how much fish can be taken.”

Geoff applauds the introduction of cameras on fishing boats, which will be phased in from next year, and would also like to see a zero by-catch policy implemented.

From the consumer’s perspective, he suggests checking Forest & Bird’s popular Best Fish Guide, which highlights the most at-risk fish stocks.

“It’s a few years old now so we’re hoping to update it, but it can give consumers more confidence when visiting the fish shop.”

And once you’re there, ask questions, he says. “Ask them if the fish has come from bottom trawling and about the fish’s carbon footprint. As a rough guide, usually orange roughy and hoki are fished via bottom trawling. And keep asking those questions because, while you might not get an answer, it shows that you’re concerned and retailers will soon get the message.”

Know someone who might enjoy this?

Good living

See all-

March 2021

In review

-

March 2021

Manaakitanga – more than just hospitality

-

March 2021

Land, sea and myth: Revisiting Hawke's Bay

-

July 2021

Breaking bread at Everybody Eats